Bouncing Teeth: 6 Jellies You Must Try in Hong Kong

From neon pig uteri to bodacious pomelo peels, Cantonese cuisine excels at creating memorable jellies from ends that are elsewhere tossed.

There are many reasons to love Cantonese dim sum, but if your fixation, like mine, is the translucent, snappy skin of har gow (crystal shrimp dumplings), or the unctuous chew of cheung fun (rice rolls), or the gnawing, gummy-bear-feel of chicken feet… Hong Kong has a lot more of where that came from.

I’m calling all of these foods jellies - striking in appearance, ambiguous, glossy forms that were born from resourcefulness and craft, persisting in part due to their perceived benefits in traditional Chinese medicine. In the Eastern practice, balancing one's energy (qi) through cooling (yin) and warming (yang) foods aids digestion, skin health, circulation, and the like.

I was at a loss for words trying to accurately describe the spectrum of jellies in their chews, probably because the American vocabulary has few words to describe these textures. But in Cantonese, as I learned from a guy shotgunning grass jelly, one of many ways to represent this beloved niche of sensations is daan ngaa (彈牙), literally, ‘bouncing teeth.’

Braised Pomelo Pith

When landing at Hong Kong International Airport, spend some time in the arrivals terminal admiring the dim sum gallery of Ho Hung Kee--a restaurant that began as a street food stall 70 years ago, now an affordable 1-star Michelin establishment. Here, your first few bites in the country can be Cantonese braised pomelo pith with shrimp roe (虾籽油皮), an old-school dish that has become increasingly harder to find in a time with less scarcity mindset.

This might be because of the meticulous preparation: thick, fibrous sheaths of pomelo skin are first repeatedly soaked overnight, rinsed, and blanched to leach out bitterness. Then, the pith is braised in a deeply savory soy + red bean curd broth until it yields elegantly like sculpture medium to a spoon, saturated with comforting flavor to its brim.

In the words of Chinese food scholar Fuschia Dunlop, “It is hard to imagine how, or why, anyone thought of turning the unpromising middle layer of this fruit about as appealing in its raw state as cotton wool – into something so magnificent. But… in China such startling culinary imagination and technical ingenuity is typical.”

Double Skin Milk

The fogged-up windows of cha chaan teng (Hong Kong-style cafes) like Australia Dairy Company are stacked from head to toe with trays of double skin milk, shuang pi nai (雙皮奶), a warm-held jiggly pudding, doled out quickly to a constant stream of visitors. The pudding is a pearly white, loose set custard without a trace of egginess, made from just egg whites, fatty milk, and sugar. Its surface has a gossamer milk skin (the first of the ‘skins’; the second being the custard underneath), which ripples when jiggled, and a warm spoonful diving in barely holds together, giving off a concentrated, thick flavor of rich cream and the slightest sweetness.

To enjoy it, I’d actually suggest a day trip outside of Hong Kong to Macau, an hourlong ferry away. At Leitaria I Son (Yee Shun Milk Company), a pure canvas of milk pudding can be garnished to order in about twenty ways, from served warm with starchy lotus seed (pictured) to cold with apricot juice, all while contemplating Portuguese colonial influence.

Interestingly, this dish isn’t an Asian rendition of European custard, as egg tarts were; rather, double skin milk evolved independently as a way to extend the life of buffalo milk in Guangdong, the province of mainland China closest to both Hong Kong and Macau.

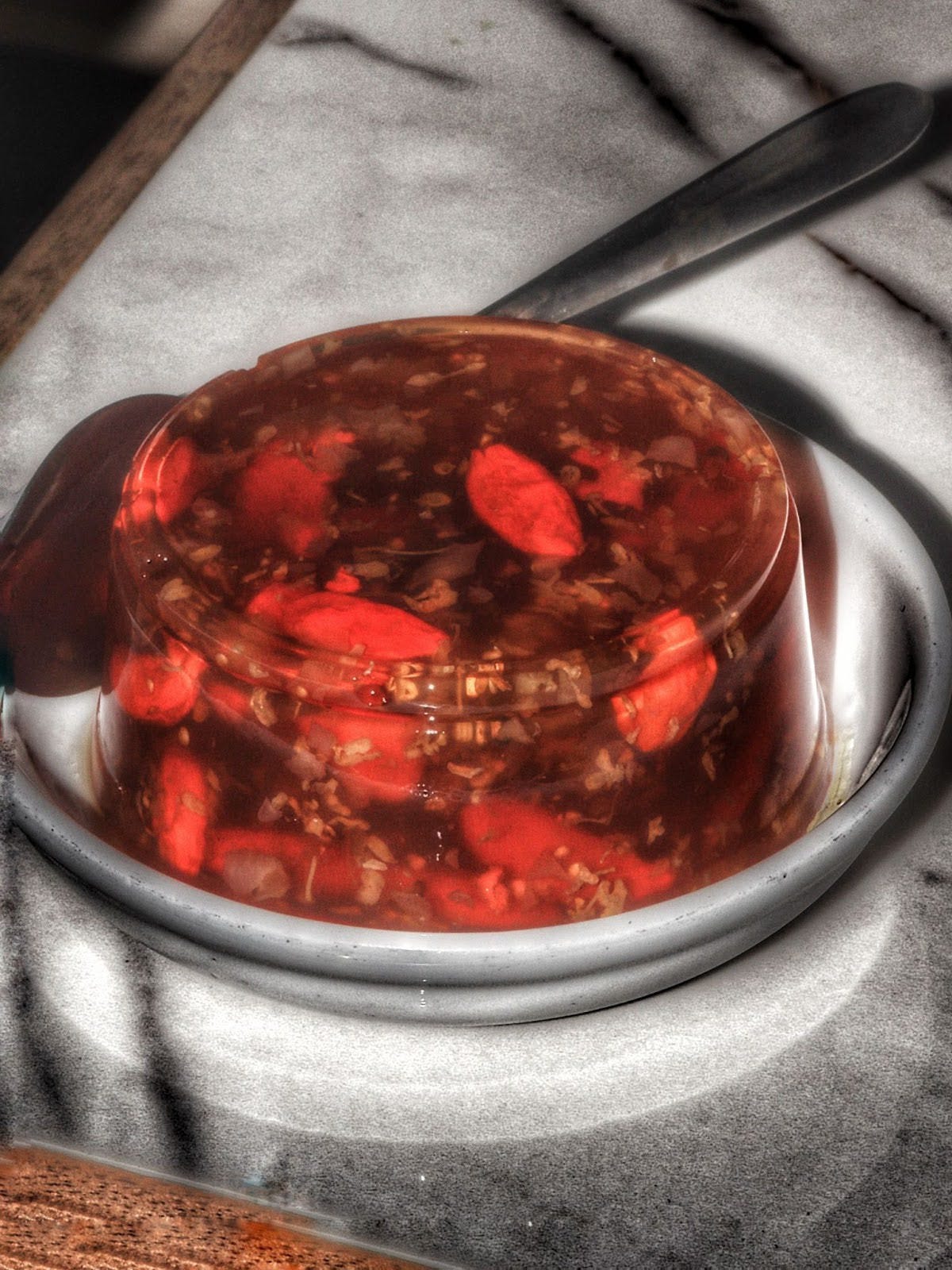

Osmanthus Jelly

Perhaps the right way to close out a succulent dim sum meal is with an equally bouncy dessert. An herbal tea jelly, such as from loranthus, osmanthus, or Chinese mesona (the ‘grass’ in ‘grass jelly’) is a beautifully sculptural choice.

In the osmanthus preparation, the amber, honeylike tea from the flower is gelatinized, stiffly suspending plump goji berries and, if you’re lucky, medlar--a resiny, fig-like, ochre fruit from the oak tree. Imagine the botanical sweetness of boba, sitting like a grand aspic centerpiece in front of you. Now, feel good seeing it: traditional Chinese medicine encourages osmanthus for dispelling heat and improving complexion.

Fish Maw

Fish have a little party trick: each one carries a balloon inside its chest. This balloon allows them to direct their motion while swimming, floating up and down, through inflation and deflation. This organ is called the swim bladder or maw (魚鰾), and when harvested from meaty fish like sturgeon and dried in neat stacks, can go for $1k a pound.

The elasticity of this muscle makes for a spectacularly spongy and tender guest star in steamed dim sum dishes--a shining, brothy, briney accompaniment to something as simple as chicken thigh and shiitake mushroom. Maw is said to support fertility, though Western medicine is unsure how; ironically, the bladders also were used as condoms in the ancient and Middle Ages.

Regardless of their health power, maw and jellies of a similar vein, like abalone, shark fin, bird’s nest, tortoise powder, and sea cucumber, have staying power. They’ve earned an unforgettable place in Asian hearts, palates, and yearly rituals. This taste has been blamed for overfishing, inflation, and endangerment of the species, and abroad, exoticized with distaste or bragging rights. I’m not sure what the solution is, or how to write about it as an outsider. One could argue the American version of this ended up resolved as factory farming and kids wrinkling their noses at lunchboxes that smell like anything other than chicken nuggets.

Braised Pig Fallopian Tube

You’ll remember it when you see it on streetcarts: neon orange, round, and as cute as giant, cartoonish macaroni shells. Google translate for sang cheong 生肠 returns raw sausage, but this characteristic shape is pig fallopian tube, or sometimes, uterus or womb, with amorphous probability. On a scale of offal gaminess, this cut is tamed to a surprisingly gentle, coffee-like sweetness, with help of a holy grail braise of cinnamon, star anise, and orange dye brine.

The braise tenderizes the chew as well; instead of the resilience of tripe, fallopian tube is somewhere closer to the snappy gelatinousness of tendon or cartilage. I’d call it a dessert if I could. It checks out that it’s said to support female fertility.

Snake Soup

As told by a beautiful girl I sat next to for claypot rice one night, the secret to youthful skin and warmth in winter is she geng (蛇羹), a seasonal snake soup. She pointed to me a stall across the street stocked with large glass jars, preserving coiled, army-green lengths, as thick as a forearm in some places and as thin as a pencil in others.

If you’re lucky, you’ll see the meat stripped by hand into long, yarnlike strands. The soup is glassy and viscous, like ‘ice jelly’, or bingfen (冰粉), both because of the meat and also to a starchy thickener, often water caltrop seeds. In taste, it’s serenely clean, yet savory, in part thanks to razor thin-cut lemon leaves on top. The meat, as diplomacy goes, ‘tastes like chicken’. Some versions use up to 5 types of snakes, making for a medley of pink, beige, tender, and dry. I have a phobia of snakes, but nothing is scarier than a life without vanity.

In Hong Kong in the 1900s, the soup was a popular delicacy. Today, there are fewer than 20 producers in the region. There’s an ongoing struggle to pass on the skills needed for an often-dangerous craft, in a world with people already eager to otherize cultures as dog-eaters.

Why do we travel, and how do we do it right? Is one not supposed to want to meet, hold onto, and celebrate all the undiluted colors and cultural vestiges of communities, especially the parts that aren’t in line with our own tastes?

The next time you find yourself in Hong Kong, I hope you feel your best and celebrate the bounce of doing so.

This piece was written by Sangita Vasikaran. Based in New York City, USA, Sangita is likely making a matcha latte at any given moment.

Funny Table is an independent food publication and video channel dedicated to teaching you more about what you eat. We’re a small volunteer team committed to telling stories that reflect the diverse voices, cultures, and communities that shape what’s on our plates. Every share, comment, like, and subscription helps us keep going.

Enjoy educational media and stories about food? Check out our videos on YouTube and Instagram for more.

Liked this piece? Let us know your thoughts!